By William F. Haenn

December 1916 saw the very last submission of the “Post Return”, a monthly report of vital statistics submitted by every post, camp and station in the U.S. Army for over 110 years. Historians have been frustrated ever since to find any single source which duplicates the essential data found in the post returns. It takes considerable digging, patience, and an element of luck in order to pick-up the story of Fort Clark after 1916.

On April 2, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson went before a joint session of Congress to request a declaration of war against Germany. Wilson cited Germany’s violation of its pledge to suspend unrestricted submarine warfare in the North Atlantic and the Mediterranean, as well as its attempts to entice Mexico into an alliance against the United States, as his reasons for declaring war. On April 4, 1917, the U.S. Senate voted in support of the measure to declare war on Germany. The House concurred two days later. Before entering the war, the U.S. had remained neutral, though it had been an important supplier to Great Britain and other Allied powers. When the United States entered the World War it had been raging since August 1914.

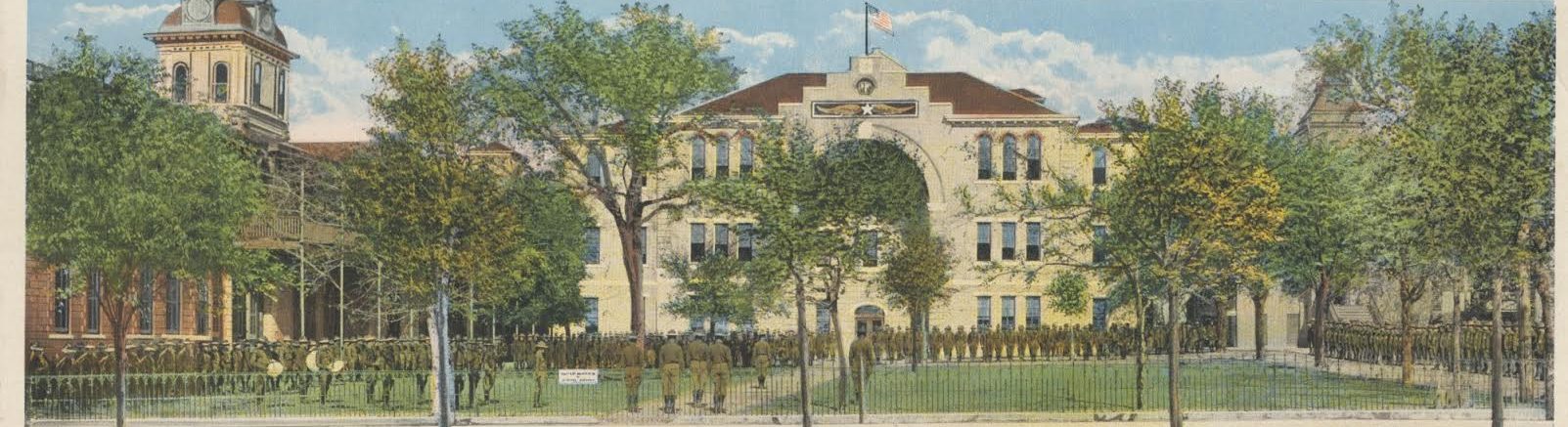

The United States, as late as 1917, depended on a small regular army of 100,000 men. After the passage of the Selective Service Act in May 1917, 2.8 million men were drafted into military service. In the spring and early summer of 1917, Fort Clark was garrisoned by one troop of the 14th Cavalry and a small compliment of command and staff. The sleepy rundown antebellum post so far from the flagpole at the War Department would soon experience a renewal of military preparedness and soldiers in numbers not witnessed since its glory days of the Indian Wars, when Fort Clark was the largest post in Texas.

To meet the needs of war, the U.S. Army’s Surgeon General, Major General William C. Gorgas (1), presided over an enormous expansion of the Army Medical Department. Fort Clark was chosen as a training station for a Medical Division, consisting of four field hospital companies and four ambulance companies, with a total of nearly 1,000 officers and men assigned. Mobilization construction began just south of the main post on two-story wooden barracks and requisite support buildings to accommodate the anticipated ten-fold increase in the fort population.

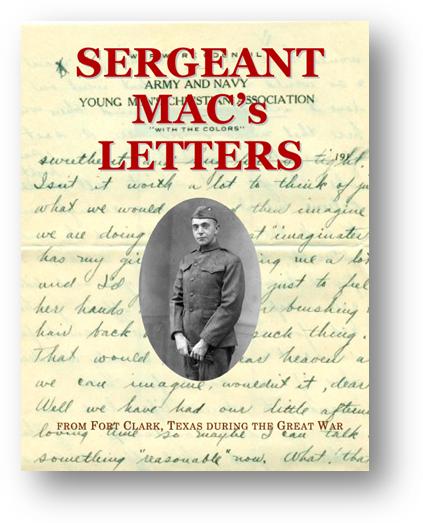

Cadre began arriving at Fort Clark in July 1917, followed by a steady stream of recruits to fill the medical units training at the post. By a stroke of incredible good fortune we have the letters of one of the soldiers who served at Fort Clark during this period. Maynard H. McKinnon, known affectionately to his fellow soldiers as “Sergeant Mac”, served at Fort Clark in Ambulance Company No. 7 from July 1917 until March 1918 during the national mobilization for World War I. Sergeant Mac’s letters illuminate a period of Fort Clark history which up to now was only a shadow at best. The infantry and cavalry regiments are well-known to us, but we did not realize Fort Clark was a training station for medical units, both motorized and mule-drawn ambulance companies, in the Great War. His observations and experiences at Fort Clark are worth reading for their candor and simplicity while continually reminding of the timeless experience of being a soldier (2).

In addition to classroom instruction on medical subjects and practical exercises applying field medical doctrine, the medical units training at Fort Clark also underwent grueling physical conditioning in preparation for the rigors of combat on the Western Front. Twenty-five mile hikes with full pack were commonplace as were repetitive drills in erecting the massive hospital tents then in use. During one exercise a patient evacuation system was setup which started at the base of Las Moras Mountain seven miles distant and ended on the parade ground. Many hours were spent as well instructing soldiers on the newest horror of warfare…poison gas, including a lecture on the subject for all non-commissioned officers by a Captain Felicquat of the French Army.

To reduce the inherent risks associated with all work and no play, what little free time the soldiers had was occupied with athletic contests between units, army band concerts, moving picture shows on post and in Brackettville, and time spent in facilities where a soldier could just relax, read, or write a letter home. Football games were the most popular spectator sport and each unit fielded a team. Competition was sharp and in one case described as, “… at times looked like a university game.” Track and field meets and boxing matches were also common in association with National Holidays when the soldiers had several days off in a row. In August 1917, the first reading and writing room for the soldiers was opened by the Ladies Guild (3). By late Fall a large Y.M.C.A. (4) building was constructed on the parade ground, which opened its doors on November 24, 1917. The facility was formally dedicated by the Commander of the Southern Department, Major General John W. Ruckman on Sunday, December 2, 1917. A massive cleanup of the post took place the day before and the Post Quartermaster Sergeant noted it was the first since 1907. That same day Sergeant Mac wrote, ”It’s a wonder I can think at all for this place is a bedlam, for the piano is going and not always in harmony & a bum quartet and the victrola going and someone running the slide up & down that makes it fast & slow, soft or loud and the room is full of card & checker players and all talking. Such is a Y building on Sun. afternoon. But everyone likes to come here as we have had nothing of the sort and all can do as they like and make all the noise possible just so they don’t tear down the building.”

Other notable reliefs from the tedium of training were the memorable meals served on Thanksgiving and Christmas. A menu remains from the Field Hospital No. 7 Thanksgiving dinner on November 29, 1917, which reflects a welcomed departure from the usual bill of fare…boiled everything. “Good eats” were indeed a rare occurrence. Sergeant Mac frequently notes he supplemented his meager army rations with an occasional Hershey bar, sandwiches purchased in Brackettville, and the always appreciated contents of food parcels from home.

The new and popular entertainment phenomenon of “movies” was well represented in Brackettville, which boasted two movie houses, and on post where films were shown regularly at the Y.M.C.A. building. In fact the first film shown at the “Y” was “The Dawn of Freedom”, a Vitagraph picture in five reels, parts of which had been filmed at Fort Clark in 1914.

(1) In 1880, when he was a first lieutenant, Gorgas served at Fort Clark as the Assistant Post Surgeon.

(2) We are working with The History Press to hopefully publish the Sergeant Mac Letters, as a Friends of the Fort Clark Historic District centennial project.

(3) The Ladies Guild originated in England as an organization promoting women rights and calling for an end to all wars. In the United States at the outset of the Great War the guild was more associated with local churches and soldier relief activities.

(4) When war was declared in 1917, the YMCA immediately volunteered its support, and President Woodrow Wilson quickly accepted it. The YMCA assumed military responsibilities on a scale that had never been attempted by a nonprofit, community-based organization in the history of our nation and would never be matched again. It was at the conclusion of that war that the military services began to institutionalize the massive human services work carried out by the YMCA.

©2016 William F. Haenn